Taiwan: Asia’s next creative powerhouse?

How come we don’t read more about Taiwan?

Well, we know the reason, but really, of all the Asian Tigers, Taiwan has arguably been the most successful in handling the transition from autocratic rule to the type of society that Richard Florida would approve of (and Luc Besson too).

The streets of Taipei are positively littered with teahouses, bookstores and indie bars. All the innovation mandarins elsewhere in Asia tasked with moving their economies up the value chain would do well to take note.

At the heart of this transition is an enlightened cultural policy, but it wasn’t always this way.

In the beginning, Taiwan was no different from other East Asian societies, where cultural policy went hand-in-hand with nation building.

From the end of the Chinese civil war to the 1970s, the KMT's cultural policy was concerned with convincing the Taiwanese that they were in fact the real China.

As Mao and the Cultural Revolution laid waste to China's ancient culture, the KMT cast itself as the guardian of China’s heritage.

Adding legitimacy to its claim was the National Palace Museum in Taipei, where treasures from Beijing’s imperial palaces, evacuated from the Forbidden City to Taiwan during the civil war, were safely displayed.

In this age of homogenisation, a centrally-dictated, semi-invented pan-Chinese identity took precedence over local ethnic identities. The masses were encouraged to take up certain Chinese folk dances and specified forms of opera as amusement, and any cultural expression that strayed from this homogenous narrative was actively suppressed.

In the 1970s, civil society began to pose more challenges to the KMT’s military rule. Simultaneously, there was an awakening of a Taiwanese consciousness. The Taiwanese public wasn't buying the Chinese identity that the KMT was trying to impose from above. Opponents emphasized Taiwan’s pre-1949 history, its waves of colonization, its aboriginal cultures and its links to Southeast Asia.

In response, there was a transition to democracy and devolution of power, with the KMT establishing cultural centers in every provincial city. In a break with the past, the new cultural policy focused on building community ties at the grassroots level.

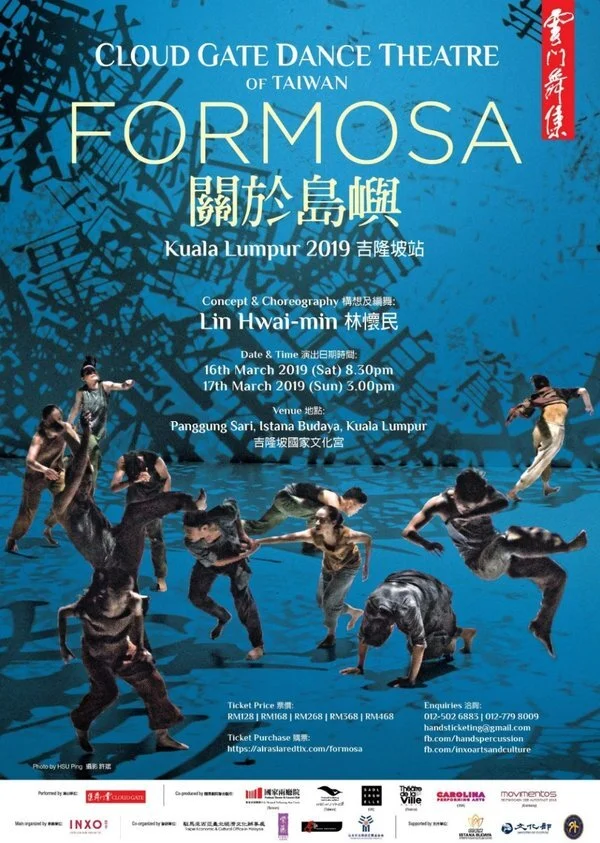

It was during this period that the world-famous Cloud Gate Dance Theatre was born, which has since become a symbol of Taiwanese (not Chinese) identity.

A promotional poster for a Cloud Gate performance. The independent Republic of Formosa existed in a brief interregnum between Qing and Japanese control from May to October 1895.

It’s interesting to compare Taiwan to South Korea, another Confucian democracy in East Asia. Here, the authoritarian state continues to direct cultural policy, and the arts lack the sort of broad-based social legitimacy that they enjoy in Taiwan. (Taiwan, unlike South Korea, has forgone the prestige projects—the starchitect-designed billion-dollar arts museums etc.—that are beloved of cultural bureaucrats in Asia.)

The evolution of cultural policy in Taiwan has been accompanied by a growing understanding that “Taiwan” is no more a monolithic entity than “China.” Modern day Taiwan encompasses more than just the Mainland émigrés and earlier Hokkien immigrants. It includes Hakkas, aborigines, and more recent immigrants from Southeast Asia. From the initial conception of Taiwan as a Chinese nation, today’s Taiwan has evolved to enshrine multiculturalism in the constitution.

Ironically, Asia’s only non-nation state may be the most sophisticated nation state of all.