Pick a side

We're all rational people of science, right?

We believe in evolution and all the rest of that stuff.

We certainly don't believe in the supernatural.

We are resolutely, one hundred percent modern.

But sometimes, we're beset by a vague unease, a sort of creeping suspicion that we're not, in fact, in control. This manifests itself in odd ways: say, we feel something cold brush up against us in the dark; or, wait a minute, did I really leave that glass there? And sometimes that sense of anxiety is so much stronger, as when we are faced with the grave illness of a loved one.

Back in the old days, when faced with this existential dread, we gave it a form and a name and then propitiated it with prayers and offerings in the hope that it wouldn't harm us. One name in one cultural context (Japan) was "Yōkai."

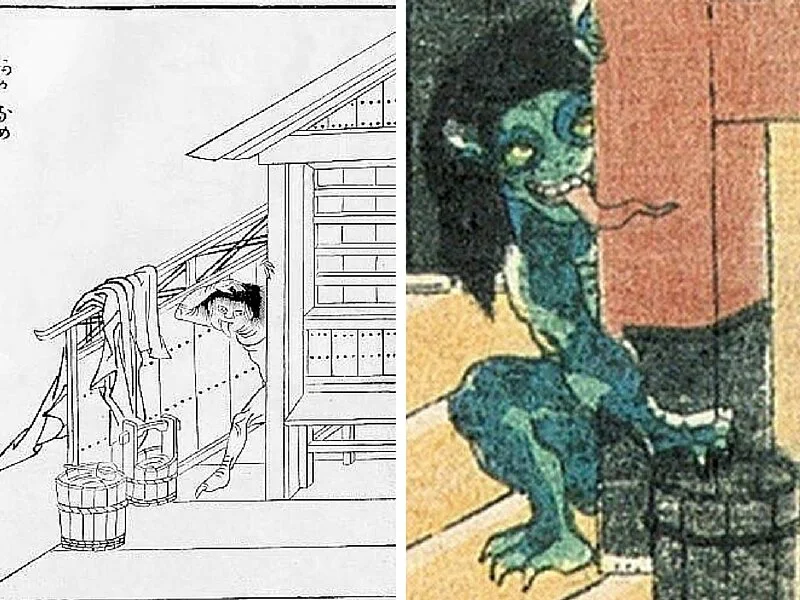

The yōkai of the Muromachi period (1336-1573).

Yes, those kawaii little pocket monsters whose names your kid can rattle off.

"Yōkai" is an umbrella term for a spectrum of supernatural beings, ranging from the benign to the truly malevolent, propitiated by all manner of Japanese, sophisticated and not, since the dawn of time.

To give you a sampling, there's Tanuki, and Kitsune, a shape-shifting raccoon-dog and fox respectively. Then there's Tenojame, the ceiling-licker. It comes out of the darkness on cold, winter nights and laps away at any accumulated frost or dirt or spider webs clinging to the rafters. You'll know the next day if you have had a visit, from the dark streaks it leaves behind, evidence of its long, red tongue being dragged along the ceiling. Then there's Azuki Arai who washes azuki beans in remote mountain streams (shoki! shoki!) while singing about eating human beings.

Akaname, the yōkai who likes to hide in dark toilets with no light switch, through the ages.

When Japan entered the Age of Reason at the beginning of the Meiji Restoration, the official policy was that such "superstitious nonsense" was not to be tolerated any longer. Yōkai were relegated to the museums, along with other relics of the unscientific past.

But that existential dread never went away. It came back, stronger than ever, during World War Two, when millions died without reason. And what did the poor people have to give them succor in their darkest hour? Science?

One young Japanese soldier, Shigeru Mizuki, who lost his arm in a battle in Papua, was largely responsible for bringing the Yōkai out of the museums after the war, back into the lives of the people, where they had always belonged.

Yōkai today, from the Mames Studio.

Yōkai for the modern age had to be given a modern form. It wouldn't do to find some old print-maker from the old days. That would mean that Japan was still traditional, and everyone knew it was not, even as post-war regeneration marched on relentlessly. Tear down the old, make way for the new. The hip makeover made it acceptable for the public to embrace the Yōkai once more. This time, it was done a little ironically, a little skeptically, but that is the modern way. Secretly, of course, everyone was still hoping for some protection in the dark.

Sources:

Michael Dylan Foster and Shinonome Kijin in The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore, 2015.