The other Manchurian incident

Here’s a test of your knowledge of World War II: Where did Japan suffer the most casualties? The answer is not Nagasaki or even Hiroshima, but the colony of Manchuria, where a quarter of a million Japanese died, eighty thousand of them women and children.

The Japanese Manchurian experiment is a story of self-delusion. It is a story that should be taught in history classes everywhere, but especially in developing Asia, because it illustrates the folly of unthinkingly following growth models developed in a different context.

According to Louise Young, a Western historian of wartime Japan, it was the maturation of the modern/ Western institutions that had been imported into Japan, and not their stunting, that led to Japan’s imperial expansion. In the 1920s and 1930s, Japan concluded that it could only compete in a world order dominated by Western imperialism with an empire of its own.

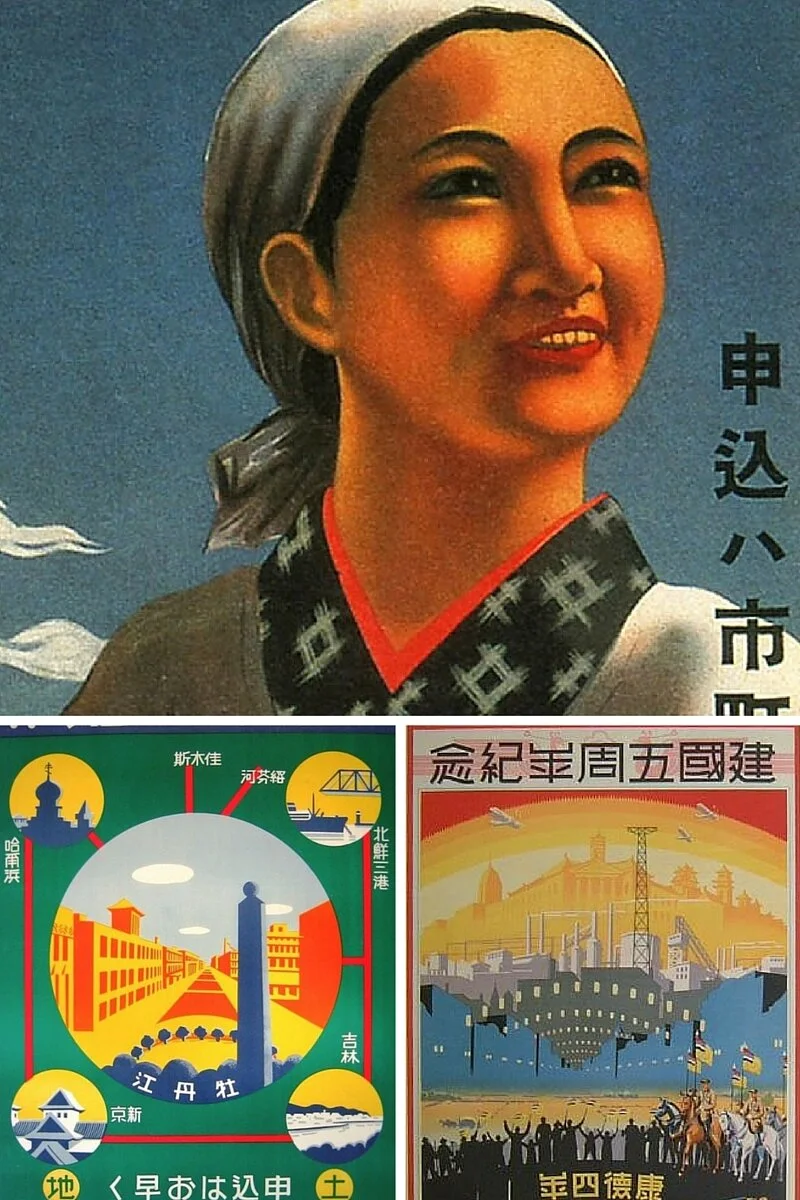

For imperialism's advocates, Japan had to take over where Great Britain left off as the leading nation of the world. Just as Anglo-Saxon settlers had colonized “unpopulated” swathes of the planet, Japanese settlers had to do the same in Brazil and Manchuria. From these bases, Japan could take over the whole of South America and Asia.

Much of the rhetoric around Japanese emigration was reminiscent of romanticism around the American West. It was thought that sending Japan's farmers--not its petty businessmen--to settle overseas was the only way to implant an “ineradicable Japanese racial influence.”

Despite the propaganda, however, Japanese villagers remained suspicious of emigration, and rightfully so. Manchuria was not an easy place to farm. The work was labour intensive, and the crop season was short. The thirty million Chinese who were already there could do the work cheaper and more efficiently.

It was only after the Great Depression set in that the numbers of Japanese emigrants to Manchuria picked up. Officials would go personally to the homes of villagers in financial trouble to convince them that paradise awaited them in Manchuria.

But why was the government so keen on sending settlers to Manchuria, knowing how difficult the conditions were? And once they were there, why did the governing Kwantung Army settle them directly in harm’s way, dangerously close to Chinese and Soviet forces?

Worse still, why did they encourage new emigrants all the way up to a few days before Japan's defeat in August 1945?

In the end, Japan abandoned the settlers, leaving them to fend for themselves. Many committed suicide en masse and desperate mothers begged merciful Chinese families to adopt their children. If the Soviets and Chinese didn’t kill those left behind, the cold and infectious diseases did.

When they set out, the Japanese had a mission civilisatrice, much like other Western powers. They even built a university in Manchuria and talked about uniting the Asian races.

Unlike the Western powers, however, the Japanese in Manchuria suffered as much as those they colonized. Imperialism had been a very bad idea for the Japanese, in other words.

Today, no respectable intellectual in Asia would advocate for such discredited Western models. Now we say that the only way to compete in the world order is through accelerated economic development. But given the population numbers here, the environmental impact of Western-style development in Asia could be disastrous. We never learn.

Sources:

Mayumi Itoh in Japanese War Orphans in Manchuria: Forgotten Victims of World War II, 2010.

Louise Young in Japan's Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, 1998.

Sandra Wilson in "The 'New Paradise': Japanese Emigration to Manchuria in the 1930s and 1940s," The International History Review, 1995.

Phyllis Birnbaum in Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy, 2015.