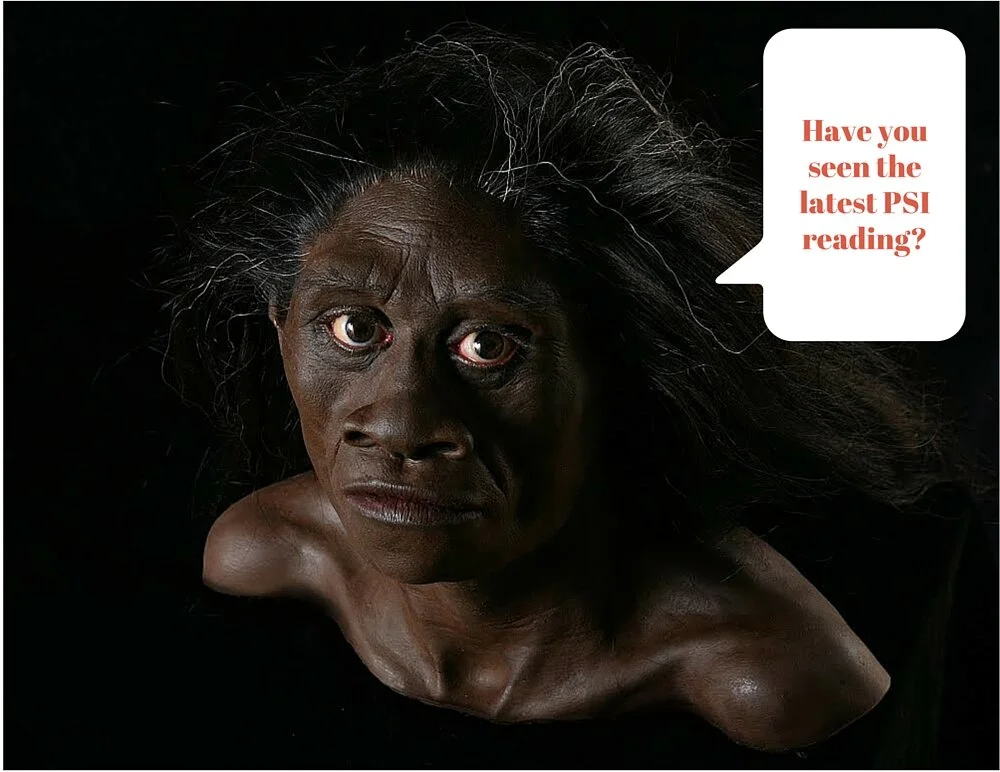

Pondering the haze

The Nage people on the Indonesian island of Flores have a legend about wild humanoids known as the Ebu Gogo. The Nage hunted down and exterminated the Ebu Gogo – the name means “grandmother who will eat anything” – ostensibly because they stole food and kidnapped Nage children.

According to the legend, Nage villagers tricked the Ebu Gogo into accepting gifts of palm fibres. Once the Ebu Gogo had taken the fibers into their cave, the villagers threw firebrands into the cave, whereupon the resulting fire and smoke killed off all but one pair of survivors.

These days, anyone in Singapore or Western Malaysia could be forgiven for feeling a bit like the Ebu Gogo as we choke on a toxic haze that has resulted from setting fire to the very same gifts of the palm tree.

Ironically, despite what Darwin might tell you, we're not much smarter about these fires than our humanoid ancestors. No one seems to know exactly who is doing the burning – whether existing plantation owners, many of which are incorporated outside Indonesia, or local landowners looking to cash in by selling cleared land to the plantations.

Either way, the financial incentives are driven by the palm oil business, which is in turn driven by companies based in Singapore and Malaysia, who in turn pay dividends and taxes that benefit, well, all of us.

The most instructive element of the analogy is that the Ebu Gogo could not evade the smoke and resolve the conflict, because they were stuck in their cave. The Southeast Asian haze is just one of many transnational environmental and social issues that are emerging in a world with increasingly integrated cross-border economic activity.

How can any single nation-state effectively address this kind of crisis, when many of the causes are elsewhere? And what incentive does a state have to do so, when many of the impacts are felt elsewhere? Such challenges to the nation-state are vexing – arguably even more vexing in a part of the world where the very concept of the nation-state is a relatively recent transplant with no historical context or analogue, and where effective state power diminishes with distance from the center.

Giving the state extraterritorial powers does not seem to be a viable solution. In 2014, Singapore passed the Transboundary Haze Pollution Act, which enabled criminal and civil actions in Singapore against entities whose activities – wherever they occur – contribute to incidents of air pollution in Singapore.

The current haze crisis suggests that this law and the powers it contains have not provided a deterrent.

It is not easy to see what kind of international regime might arise to assist with the resolution of this type of problem. Efforts to combat climate change are mostly about nations controlling emissions within their own borders.

But if the legend of the Ebu Gogo teaches us anything, it is that if we continue to stay in our caves, the prognosis is not good.

Sources:

“The Little Troublemaker,” New Scientist (Vol. 186 No 2504), 18 June 2015.